|

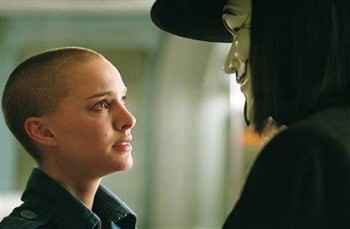

The Wachowski brothers have done it again, and by "it" I mean "written a big slow-motion fight in a subway station into a film." So let's for the moment forget about their involvement in this project, shall we? Mind you, this isn't the easiest thing to do. It should be; after all, what else do we have here? A story by Alan Moore, one of the few exemplary writers amongst the legions of slugs in the bloated carcass of comic book authorship? Hell yes. Leading roles by Natalie Portman and Hugo Weaving? Damn straight. A dark, politically charged tale about the evils of powerful governments? Sure, I'll watch that. But what the ads want us most to realize is that this film comes from "the creators of the Matrix trilogy," the least interesting factor involved here. For all its popularity, The Matrix was little more than a more expensive version of all those "evils of virtual reality (which has absolutely ceased to be a topic of anyone's conversation these days)" flicks that were springing up like mushrooms in the early '90s, with a lot of rather poorly articulated philosophy and poorer science layered onto a collection of visual images finely calculated to make the viewer wonder exactly when someone would be rolling out a luscious new fuel-injected vehicle that they would be expected to lust after to the point of an ill-advised impulse purchase.  The central focus of V for Vendetta is the issue of terrorism, and quite specifically, whether or not terroristic methods are ever a justified means to effect change. While they did not write the story or characters, merely having adapted them, one must at least admire the Wachowskis for having the considerable spine to address this subject at all in our modern political climate. Many people are not going to embrace the story of our protagonist's battle against a repressive government with especially wide-open arms. The titular character, known only as "V," is a masked avenger of sorts, wearing an all-obscuring mask of a smiling Guy Fawkes, the would-be seventeenth-century revolutionary who attempted to blown up the houses of the British Parliament with gunpowder. In the first few minutes, we see V fight off and kill a group of government thugs who are attempting to have their way with a wayward young girl named Evey, which is good, and then to blow up the statue of Madam Justice amidst many skyrockets, the goodness of which is somewhat more debatable. As the story unfolds, V will employ many audacious methods for attempting to subvert government power and incite the will of the people to rebel, while gradually killing off a succession of individuals against whom he holds an old grudge. Evey Hammond, having been saved by V early on, is torn between her nonviolent tendencies and the reality of the world she lives in, and wrestles with the matter of whether or not V's objectives and methods are necessary or evil. Given the complete lack of facial acting, Weaving gives enough personality through vocal acting alone to elict a sense of character, though some of the physical acting is still attributable to James Purefoy, who bowed out of the role partway through production. Natalie Portman shows once again that, freed from the constraints of Star Wars dialogue, she's quite a capable actress, able to elict viewer sympathy almost effortlessly. She's also drop-dead gorgeous, with or without hair. Stephen Rea is excellent as Finch, police inspector assigned to track down V and a man with a conscience. The real star, however, isn't even listed in the credits, at his own insistence. It's hardly a coincidence that the best and most powerful parts of the film are those parts which are lifted intact from Alan Moore's graphic novel. Whenever it strays from that material, it's almost always to the story's detriment, even in the less broad areas. Evey now has a job and seems reasonably well-off, instead of being forced to attempt to turn tricks in order to keep her head above water. V's speech over the television castigates the oppression of government rule, but in the book he more pointedly chastises the citizens themselves for consistently choosing to hand control of their lives over to corrupt men. The government itself is more obviously evil now, making the matter of V's crusade far less morally questionable. There's now no mention of ethnic cleansing; the only part of that notion remaining is the persecution of homosexuals, most poigniantly in the scene where Evey reads a letter written by a concentration camp victim, a letter notably taken almost verbatim from Moore's written word. The Great Leader himself, an unapologetic fascist, was a man who was, as written by Moore, a very lonely and sad individual who honestly believed his actions were at least necessary for a safe society, however evil they might have been. In the hands of the Wachowskis, he becomes little more than a unidimensional, undeveloped cartoon who barks a lot and seems more like a Bond villain than a real person with feelings or an actual viewpoint of any kind. Out of all the contributions here, the Wachowskis' are honestly the least noteworthy. It's also rather striking, given the issues raised in the novel, that the word "fascism" (or any derivatives therof) doesn't appear in the film script at all, and, but for the quoting of a Sex Pistols song title, neither does the word "anarchy." It's clear that V has many a bone to pick with the regime of his time, but oddly seems to have no specific political views of his own to offer in contrast, a fact which was doubtlessly a major factor in Alan Moore's publicized disowning of the film. The plot as it now plays out feels much more like an indictment of recent American politics, with its criticisims of conservativism, Christian fundamentalism, and vague references to a war started by the US that spilled over to affect the rest of the world, as well as a barely-disguised stab at Rush Limbaugh/Bill O'Reilly types. A bold thing to do in our day and age, perhaps, but a clash of ideologies requires the presentment of an opposing set of values, and aside from the spirit of revolution, our hero doesn't seem to possess one anymore.  First-time director James McTeigue, a second-unit veteran of the Matrix trilogy, directs the film adequately enough but with little sense of style, except in the places where the shadow of the Matrix style threatens to overwhelm the screen. I'd have rather seen the likes of Terry Gilliam or perhaps Ridley Scott at the helm here; it would've spared us the hyper-clinical Matrix look and likely would've been richer. The film in its beginning feels rather fractured, and it's hard to get a sense of the world we're supposed to be seeing. V's initial speech to Evey is also so proudly clever that it becomes almost uncertain as to whether or not the film is meant to be taken as serious or satire. It gets better and clearer as it goes, but there are several spots (such as V's origin story and the manner of his escape from his oppressors) where knowledge of the book is almost prerequisite to understanding what's happening. The film does, on the other hand, give Evey a bit more to do in the beginning, even if it gives her less of an arc from victim to empowerment, and there's a hilarious bit of an ill-fated television satire on the leader that plays like a skit from The Benny Hill Show and evokes much in the way of a nervous calm in the midst of the storm. There's still much to admire here, but I nonetheless miss V's eloquent speeches on the virtues of anarchy, even if I don't completely agree with them. I always thought that V for Vendetta could make a great film, and it probably could, but as it stands, it's only made a good film. One is certainly going to get more food for thought and potential for interesting after-film discussion from this movie than from most others, especially most that would fit comfortably within the action/adventure genre. But having read the book, it's clear that it could have been so much more. -review by Matt Murray Editor's note: Subsequent viewings have brought me to a much greater appreciation of this film, as I focus more on what it does instead of what it does not. My chief complaints-V's lack of a specific political view, the lack of development in the Chancellor's character, and too much Matrix visual influence-remain, but I can overlook these issues in favor of the strong emotional core the film does possess. It's also very gratifying to have a film that is guaranteed to piss off everybody I can't stand. I don't care if you're a conservative; if you don't think that a society that puts ethnic and social minorities in death camps deserves to be overthrown, there is something frighteningly wrong with you. Being anti-Holocaust doesn't make you liberal, it makes you human.

|

|

||||||||