|

Michael Crichton is a man-or was a man-who managed to build an entire career out of one basic idea. If you've seen any films he wrote or directed, or which were adapted from anything he wrote, you know which idea I'm referring to: this hardened conviction that scientists, with all their scientific noodling, will somehow ruin the world. It still hasn't happened, but we've got forever within which to see this particular brand of doomsaying vindicated.

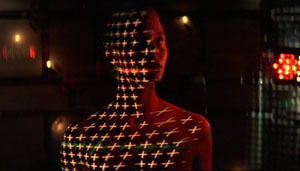

Larry Roberts is plastic surgeon to the stars, and recently, he's had a number of perfectly fine-looking female clients coming in with exacting lists of nearly imperceptible flaws they want to see corrected for the betterment of their advertising careers. After returning home from her consultation, one such example of the perennially self-dissatisfied answers a knock at her door (in her underwear, like all attractive women do), and finds herself experiencing strange blackouts. No one appears to be at the door. A minute later, her dog is found stuck in the closet, when only moments ago he'd been capering at her feet. When one last such blackout causes her to fall to her death from her balcony, the police come around to Roberts's clinic asking questions. It seems she was the second of his patients to apparently commit suicide, and when a third soon follows, he finds himself in the position of attempting to protect the fourth possible victim, Cindy Fairmont, whilst not appearing to further implicate himself. Unknown to him, a pen from his office and a button from his coat have been surreptitiously left at one of the crime scenes, and his personal files stolen. All he has to go on is a name, Digital Matrix, which seems to have employed all four women. This film is teeth-grindingly frustrating. Crichton the writer and Crichton the director aren't functioning at the same level; it's rare that a writer is so capable of sabotaging his own work. There's a lot of interesting ideas going on in here, and almost none of them get explored beyond a cursory level, certainly not with the scrutiny with which a computer scanner (and likely the male audience members) parses Susan Dey (Cindy)'s body in a key sequence. The central idea is that of digitally re-created human beings, a bold bit of foresight for a film produced in 1981, a year before Star Trek II and Tron gave the world its first real taste of computer-generated special effects. Indeed, it's a bit of an amusing coincidence that a highly successful film version of a later Crichton novel, Jurassic Park, would be the first film to present convincingly-rendered living creatures. Cynic that he was, he immediately saw the burgeoning technology as a source of possible corruption and abuse of power. The film satirizes the advertising industry-and with my enthusiastic approval, as I find advertising positively insipid-and its manipulation of viewers via the new CGI spokesmodels and precise calculations of audiences eyelines. At the same time, this next generation of ads contains hypnotic light effects intended to lull unsuspecting customers-to-be into a trance, a technology which has also been utilised as a weapon in the form of the LOOKER pistol. Even more sinister applications are hinted at, as Digital Matrix seems to have ties to a certain US senator whom they have also digitally re-created, a move which could possibly open the doors to all sorts of power abuses.

It's a shame, then, that all of these speculative ideas are almost totally sidelined by spy antics, car chases, initially interesting but ultimately long-winded and unnecessary fight scenes, and ogling Susan Dey's naked body, although I doubt any male who grew up watching The Partridge Family complained about that last one too loudly. In my mind's eye I see several film cans of Looker footage mistakenly shipped to a landfill somewhere in Burma. The plotline involving the senator is hinted at near the beginning and then isn't mentioned again until near the end, when the company responsible for all these diabolical goings-on openly exhibits their CGI congressman as an example of their new tech's abilities, seemingly undermining its potential for exploitation. Worse yet, there's never any motive hinted at for the murders of Roberts's other three patients, and the matter of his planted coat button never resurfaces. The wayside is littered with the detritus of abandoned plotlines, and the finale is a little too tongue-in-cheek to work dramatically (though it does at times work rather well comedically); it gives up on being a conflict based on ideas, and becomes simply a conflict between armed men. The final act is also baffling in the way the investigating detective utterly vanishes from the scene in exactly the way that cops typically fail to do in such circumstances. I'm personally not a big fan of Crichton's anti-science paranoia, but he nevertheless seems to be a man capable of better ideas, or at least better execution of them, than this film would indicate. When all's said and done, about the only thing Looker will be remembered for is the chance to see the Partridge Family daughter in an extended nude scene. Some might well argue that that's enough reason to recommend it, but as the scene occurs before the halfway point is even reached, it doesn't suffice as a reason to recommend actually staying until the end. -review by Matt Murray

|

|

||||||||